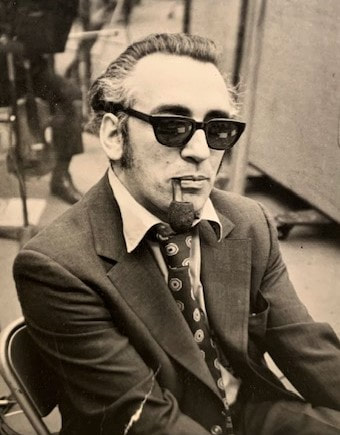

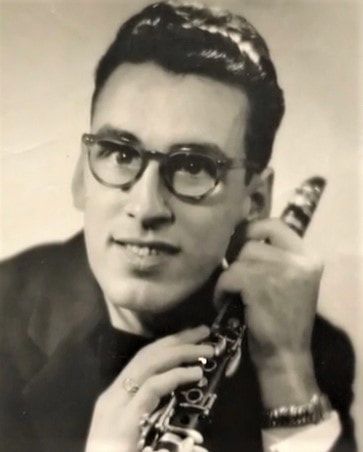

Jack Zaza 1930 - 2022

He played nine different instruments on a Gordon Lightfoot album, mandolin for an Anne Murray recording, sax for the Spitfire Band and the Guess Who, clarinet for Bruce Cockburn, oboe for Hagood Hardy, and at least eleven different instruments on six albums recorded by John McDermott – the list goes on…Sharon Lois & Bram, Ronnie Prophet, George Hamilton IV, commercials, films, TV shows…

“I never knew anyone who gushed music as openly as Jack Zaza did.” Jim Morgan

Jack Zaza, who died in June 2022 at the age of 91, was the undisputed king of Canadian studio musicians in his day. And everyone you talk to - fellow musicians, friends, family, people he barely knew - speak of him with a love and admiration reserved only for the finest among us.

According to allmusic.com, Zaza played a total of no fewer than twenty different instruments (closer to thirty according to some who knew him well) on hundreds of albums, many of them with major artists. He was among the first Toronto musicians to use the then-new Fender electric bass in recording studios. And he was very good. He played bass on the original Hockey Night in Canada theme, and was on violin AND electric bass in the 1969 Toronto production of Hair. When he retired, he sold that Fender bass to David Piltch, who never changed a thing - not even the original strings. He's still playing it that way. More about that later.

Zaza can be heard on EIGHT Gordon Lightfoot albums. On one of them, Endless Wire, he plays nine instruments (alto sax, tenor sax, baritone sax, bass clarinet, English horn, alto flute, harmonica, harmonium, shakers). Nine instruments! And that doesn’t include a couple on which he was at a virtuoso level, according to some he worked with - the mandolin and mandocello. That was saved for Anne Murray’s I’ll Always Love You album, among many others.

Before I count them up, understand that Jack Zaza played jazz bouzouki, for God’s sake. He had pennywhistles IN EVERY KEY. You try counting the number of instruments a musician like that can play. But here’s my list. Additions coming later, I’m sure. (Oh, and by the way, he played them all well enough to be on recordings with all of them!

Thirty instruments played by Jack Zaza

bass guitar - guitar - alto sax - tenor sax - soprano sax - baritone sax - clarinet - alto clarinet bass clarinet - oboe - English horn - flute - piccolo - alto flute - mandolin - mandocello bouzouki - violin - pennywhistle - spoons - shakers - harmonica - bass harmonica harmonium - accordion - jaw harp - ukulele - banjo - recorder

He played piano too, but I’ve found nothing about him playing it professionally. Yet.

bass guitar - guitar - alto sax - tenor sax - soprano sax - baritone sax - clarinet - alto clarinet bass clarinet - oboe - English horn - flute - piccolo - alto flute - mandolin - mandocello bouzouki - violin - pennywhistle - spoons - shakers - harmonica - bass harmonica harmonium - accordion - jaw harp - ukulele - banjo - recorder

He played piano too, but I’ve found nothing about him playing it professionally. Yet.

According to drummer Brian Barlow, who was a recording companion for many years, Zaza was so busy in the studios that contractors would hire him for recording sessions even before they knew what instruments would be required. They knew he’d get hired elsewhere if they didn’t move quickly, and besides, he could play just about any instrument that might be needed.

Jack’s son Paul says his dad was probably the first studio electric bass player who could read music. Typically, the only bass players who could read would be the symphony musicians who played the big stand-up bass.

“Dad was unique in that he could read anything put in front of him. That was the springboard that led to a lot of other things - he did all the studio stuff in those days.”

There are a million stories.

Paul Zaza: Hair (1969 musical), the oboe, and Lightfoot

“The biggest problem they had was that the Royal Alexandra Theatre was old, and the acoustics weren’t the greatest, and the pit band was on stage. The audience could actually see the band on the stage for the whole show. So, the sound was uncontrollable.”

“The show started with the song Aquarius, which had a bass solo introduction. The problem was, the original bass player they hired, who was NOT my father, played the bass with his fingers, which was the way most bass players played. They didn’t use a pick. Well, the sound was really low and muddy, it was swimming around the theatre, and the actor who took his cue from that bass solo complained that he couldn’t hear it. He couldn’t hear the key or the tempo. So, every time they rehearsed, the actor would be in the wrong key and tempo."

“Nobody could figure it out, so they fired the bass player. They bring in another guy. Same thing happened. They fired him, too. They get a third one in. Same thing. Fired.”

“So they’re going down the list and they get to my father’s name. The producer from New York says, ‘OK, we’ll try once more, and if this doesn’t work, we’re gonna bring in our own guy from New York, because he made it work.’ You have to realize that the guy from New York wouldn’t have had any better luck, because this was an ACOUSTIC problem. The band’s ON the stage, and the acoustics aren’t great to begin with.”

“So, my father went in, and he wasn’t into acoustics, but he had good ears. He plugs in, and after hearing the actor say again that he hasn’t been able to pick up on his cue, says ‘let me try something. I think I know what’s wrong.’

“He put a lot of treble on his amp, a lot of top-end, and he played with a pick, because he was a mandolin player. They tried it, and it was beautiful. Four bars in, and the singer comes in perfectly - ’When the moon is in the seventh house…..’ The producer jumps in and yells ‘hire that guy!’ My dad says ‘wait a minute - you want me to do the show? I’m really busy with studio work, and TV shows.’ The producer comes back with, ‘what do you want? We’ll pay you anything you want.’"

“Dad says, ‘well, how about double-scale? ‘OK. Deal.’"

But the deal wasn’t final. There was one brief scene in Hair that required about 30 seconds of violin.

‘You don’t happen to play the violin, do you?’

JZ: ‘Yes, I do actually, I was trained on the violin.’

‘Could you bring your violin tomorrow?’

JZ: ‘Yeah, I’ll bring it. So let me get this straight. You want me to play bass AND violin?’

‘Yes.’

JZ: ‘OK - remember the thing about the double-scale? Now we’re gonna have that, PLUS I’m gonna want a 50% double for playing the violin.'

“ ‘But it’s only for 30 seconds.' So Dad says, ‘OK, get somebody else.’"

Now the deal was done. Maybe not.

“Now my father was not a stupid man. He says, ‘you know what’s gonna happen - they’re gonna fire me later, and then they’ll hire another bass player who they can pay less.’ I think they’d already cut the violin part, because it really wasn’t a big part of the show.” So my dad had it put into the contract, that he, or substitute players of his choosing, would be the only bass players in Hair as long as the show played in Toronto. They hemmed and hawed, and he said, ‘fine, get somebody else,’ and finally they said, ‘fine, whatever you want, just show up tomorrow night.’

“And I ended up subbing a lot for my dad on bass. He couldn’t possibly do eight shows a week because he was so busy with other projects, and Hair ran a year-and-a-half in Toronto.”

“He made a lot of money doubling. And in the long-run, it was a lot cheaper than hiring one player for every instrument. Because he played sometimes five or six or even nine or ten instruments, he’d walk out of the studio sometimes with three or four times what other great musicians who doubled on two or three would make.”

“The oboe made him crazy.”

“The oboe gave him the most headaches, and it challenged him beyond anything that he’d ever done in his life. He couldn’t get it mastered to the point where he felt he was as good on that as he was on the mandolin or flute or sax. He’d drive to Rochester and back in a day many times for lessons at the Eastman School of Music. He couldn’t figure that instrument out on his own – how tomake the reeds, where to buy the cane, how to wrap the cane, practise, practise, practise, all this stuff….”

“Even in his 90s, after he’d sold all his instruments, and the only thing he was doing was taking care of my mother, he’d sneak downstairs while she was asleep during the day and make reeds for an oboe he didn’t have. It was his passion.”

“I was at the house not long after he died, and I went downstairs - you can imagine, it was kind of emotional…looking around, I’m seeing all these knives, and oboe reeds, all laid out on his desk, and he had this magnifying glass he put on his head so he could see all the fine detail in the reeds, and it was all perfectly laid out. What he was gonna do with them, I have no idea. He was just totally obsessed with the oboe.”

Gordon Lightfoot: "Could I sing a few songs?"

Gordon Lightfoot: "Could I sing a few songs?"

A then-unknown Gordon Lightfoot played drums under a pseudonym in Jack’s trio at the Orchard Park Tavern. Recounting the story told by his dad, Paul says Lightfoot told Jack he was also a guitar player, and would he mind if he tested out a couple of songs he’d written on the audience while the rest of the trio took a break? Jack gave him the green light.

“So the rest is history. He started singing his songs, and the audience is getting into it. It was very clear this guy could write a song. His songs were captivating.”

Soon, Lightfoot told Jack he’d have to quit and find someone else for the trio - he was getting offers and he had a record deal in the works. And he asked Jack another question. For the ages, as it turned out: “Do you know the name of a good accountant?”

“So the rest is history. He started singing his songs, and the audience is getting into it. It was very clear this guy could write a song. His songs were captivating.”

Soon, Lightfoot told Jack he’d have to quit and find someone else for the trio - he was getting offers and he had a record deal in the works. And he asked Jack another question. For the ages, as it turned out: “Do you know the name of a good accountant?”

“This guitar is my cherished possession.” - David Piltch

As of this writing on July 26, 2022, Toronto-born bassist David Piltch is the proud owner of Jack Zaza’s original Fender bass guitar, which Zaza played in Hair, and for the Hockey Night in Canada theme.

“I have the bass in my hands right now. I’m on a session right now in Los Angeles. I’ve been playing it since I bought it. I’ve used it for many, many recordings. It’s the apple of many people’s eye, they look at this bass, and you know, it’s gorgeous. It’s completely intact – it has the same strings that he had on it. I’ve never changed them. It sounds beautiful – it’s just gorgeous history. And I got it from Jack.”

“I was in a session with Jack. I was on bass, and he was on one of the woodwinds. And he said to me, ‘when it’s time for this bass to be passed on, I’d like you to have it.’

“I knew Jack as a child. I used to go to work with my father (Bernie Piltch, who was the music director for Hair) and Jack would be playing everything. My dad and Jack worked a lot together.

“Years after Jack had kind of affectionately told me in that studio that he wanted me to have it, I had heard through the grapevine that somebody was going to buy it. When I heard that, I called up Jack, and I said ‘let me buy it. He said c’mon over to his house. I’d never been there.”

“I went over to get the bass, and he had this huge spread for me. All this food. And food. And more food. I’d never socialized with him, although I’d done gigs with him. One of the great gigs I did with him was one where he was playing jazz bouzouki. I mean, who plays jazz bouzouki? Jack did! Anyway, I wrote him a cheque for the bass and took it with me.”

“I have the bass in my hands right now. I’m on a session right now in Los Angeles. I’ve been playing it since I bought it. I’ve used it for many, many recordings. It’s the apple of many people’s eye, they look at this bass, and you know, it’s gorgeous. It’s completely intact – it has the same strings that he had on it. I’ve never changed them. It sounds beautiful – it’s just gorgeous history. And I got it from Jack.”

“I was in a session with Jack. I was on bass, and he was on one of the woodwinds. And he said to me, ‘when it’s time for this bass to be passed on, I’d like you to have it.’

“I knew Jack as a child. I used to go to work with my father (Bernie Piltch, who was the music director for Hair) and Jack would be playing everything. My dad and Jack worked a lot together.

“Years after Jack had kind of affectionately told me in that studio that he wanted me to have it, I had heard through the grapevine that somebody was going to buy it. When I heard that, I called up Jack, and I said ‘let me buy it. He said c’mon over to his house. I’d never been there.”

“I went over to get the bass, and he had this huge spread for me. All this food. And food. And more food. I’d never socialized with him, although I’d done gigs with him. One of the great gigs I did with him was one where he was playing jazz bouzouki. I mean, who plays jazz bouzouki? Jack did! Anyway, I wrote him a cheque for the bass and took it with me.”

“A wacky, funny, wonderful man!” - Jim Morgan

Musician and studio producer Jim Morgan worked off and on with Jack Zaza for forty years. “I never met anybody who gushed music as openly as Jack Zaza. Such a wonderful spirit. Everybody was lifted by his presence. He was such a giving guy. Anything that Jack added to a piece of music was magical.”

“Jack booked me in his band to play with the Monkees on tour in 1969. The Monkees didn’t really play themselves, and so Jack played every instrument imaginable. I’d say Jack, have you ever played this or that instrument, and he’d say, ‘just give me 15 minutes.’ He’d disappear for 15 minutes with whatever instrument it was, and come back playing it like he’d played it all his life!”

“When I was a young fella working in the studios, I wasn’t a great sight reader of music. If I was sitting next to him during the session, he’d notice if I was having a problem. While he’s playing his own part, he’d quietly lean over and sing me the rhythm. And he did the same thing for all of the musicians around him. He'd come to sessions with whole bags of instruments. Contractors would tell him to just bring everything. If there wasn’t a part for him, he’d make something up on something that always added something fabulous to whatever the music was. He was so creative.”

“Jack booked me in his band to play with the Monkees on tour in 1969. The Monkees didn’t really play themselves, and so Jack played every instrument imaginable. I’d say Jack, have you ever played this or that instrument, and he’d say, ‘just give me 15 minutes.’ He’d disappear for 15 minutes with whatever instrument it was, and come back playing it like he’d played it all his life!”

“When I was a young fella working in the studios, I wasn’t a great sight reader of music. If I was sitting next to him during the session, he’d notice if I was having a problem. While he’s playing his own part, he’d quietly lean over and sing me the rhythm. And he did the same thing for all of the musicians around him. He'd come to sessions with whole bags of instruments. Contractors would tell him to just bring everything. If there wasn’t a part for him, he’d make something up on something that always added something fabulous to whatever the music was. He was so creative.”

“He sat down and refused to play.” - Roberto Occhipinti

Award-winning bassist, composer, and producer Roberto Occhipinti says Zaza not only played all those different instruments – he played them very well.

“It was different a generation of musicians. It’s a lost art. Whatever instrument he played - you couldn’t tell what his number one instrument was, because they all sounded like they’re supposed to. Take the oboe. There were some really good orchestral players then…but he played so well that you really couldn’t tell who was who just by listening to them. There are musicians who play three, four, and five instruments, but not nineteen, or whatever it is.”

“One of the first shows I ever played was Chorus Line. Peter Appleyard was the contractor. The conductor of the show was a very bitter man. These shows would come from New York, and they’d bring their own conductor and drummer. It was like they had to show these guys in Canada how it was done. Now most of the horn players were from the Boss Brass or Phil Nimmons’ band. They were all very, very good and experienced players. I was the youngest.”

“We get to the first rehearsal and the conductor was antagonistic right from the get-go. One of the trumpet players, I think it was Sam Noto, said ‘do you want us to follow you or the drummer?’ First shot across the bow, you know.”

“ ‘What are you talking about,’ the conductor said, ‘the drummer’s following me. You follow me!’ “

There was another festering problem.

“During rehearsals, the mics were live. The “pit” was covered, so the musicians couldn't be seen. But they could be heard. The conductor heard what he thought were musicians talking too loudly. He yells ‘stop talking!’ “

But according to musicians and others who were there, it was actually a technical problem with the sound that was making him think the musicians were talking. They weren’t.

Fast forward to the dress rehearsal the night before the show opens. There is a partial audience. Again, the conductor thinks he hears talking. His frustration boiling over, he yells again, ‘no talking!”

Occhipinti: “So here we are in the dress rehearsal, there’s an audience out there, and one of the brass players leans into a mic and says, ‘Why don’t you fuck off?’

“The conductor says – ‘who said that?’ I’m paying you to play and not talk.’ So then Jack, because this guy had been browbeating us all week, stood up, looked at the conductor, and said ‘why don’t you fuck off with that bullshit, you asshole.’

“Jaws dropped, of course, because Jack was a pretty even-tempered guy. But then he sat down in his chair and refused to play. Then there’s a five-minute lull, and we’re trying to figure out what to do. We go upstairs and we read the riot act to Peter Appleyard. We tell him this conductor’s gotta stop hounding us or we’re not gonna play tomorrow night. We quit.”

“So we’re in the show the next night, we get through it, and the guy stops hassling the musicians. That was Jack standing up for us. He was just a really great guy. He was all business, great sense of humour, a total professional.”

"I’m not sure I’d’ve lasted in the studios without Jack Zaza.” - Barry Keane

(session drummer well-known for his work with Gordon Lightfoot and Anne Murray)

“I had very little musical knowledge when I got into the studio scene…I couldn’t read music to save my life. There was more than one occasion when Jack was there to bail me out. A couple of times he was the only reason I made it through a session. Probably a huge reason why I got hired again.”

“Way back early in my career, I somehow got booked to play for a CBC Radio series that was based on music from around the world. Well, my knowledge of music from around the world was limited to whatever pop music I heard on a transistor radio or a car radio, so I was immediately in way over my head."

“The first track we played was a Greek ditty that was way up tempo, and it was in 9/8 time. I was in so far over my head I was embarrassed, it was so awkward – I had no idea what to do. And after the first take, the arranger and most of the other musicians were looking at me like, ‘what the hell are you doing?”

“During my angst of trying to figure out what to play, I did notice, sitting right outside the drum booth, was Jack Zaza, who was playing a bouzouki part. And he was stumbling and fumbling, making mistakes galore, and during the whole time he was smiling and having the best time of his life.”

“And Jack recognized what trouble I was having - he put the bouzouki down, came into the drum booth, tapped out a drum part that I could actually hear and could play. He saved my butt on that. I was then able to make sense out of the music and play something.”

“But here was a man who was having difficulty enough with his own part, and rather than spend the next few minutes before the next take trying to figure out what HE was going to do, he took the time to come in and help a struggling drummer get through the session. Talk about kind and considerate. The other thing that stands out - here he was, stumbling over his own music, but even so, he had the biggest smile on his face, and he was laughing over the challenge he had in front of him playing that bouzouki part.”

“I can remember another time we were doing an album with a major Canadian country music star. I wasn’t all that familiar with country music, although the rest of the guys were a lot more up on the stuff. Anyway, we got to a tune that everybody else seemed to know, and it just sort of fell together because everybody knew it. So I jumped in, just playing what I felt.”

“As it turned out, the major riff in this tune was falling in a different place in the bar than where I was hearing it. So somehow, I was managing to turn this simple country tune into a bizarre polka, I guess…a few bars in, the singer threw up his hands and said, ‘what is going on?’ So everybody looked at me because they knew I was the problem.”

“I looked over at Jack, because he was playing bass on the session, and he was laughing his butt off. He knew what was wrong. Jack put the bass down and came into the drum booth. He says, ‘do you know what the problem is? I said no. He said ‘the problem is you have too much “feel.” The problem isn’t you, it’s the way it’s written.’ And then he hummed the riff to me so it made sense to me. He was able to come to a young musician and fix the problem, make me feel good, and actually fill me with confidence.”

“Most of us accept challenges. He SOUGHT challenges. He learned new instruments all the time, and he had the best time when he was confronted with difficult music on instruments he barely knew how to play. He’d go learn how to play them. He did everything with such joy."

“It was different a generation of musicians. It’s a lost art. Whatever instrument he played - you couldn’t tell what his number one instrument was, because they all sounded like they’re supposed to. Take the oboe. There were some really good orchestral players then…but he played so well that you really couldn’t tell who was who just by listening to them. There are musicians who play three, four, and five instruments, but not nineteen, or whatever it is.”

“One of the first shows I ever played was Chorus Line. Peter Appleyard was the contractor. The conductor of the show was a very bitter man. These shows would come from New York, and they’d bring their own conductor and drummer. It was like they had to show these guys in Canada how it was done. Now most of the horn players were from the Boss Brass or Phil Nimmons’ band. They were all very, very good and experienced players. I was the youngest.”

“We get to the first rehearsal and the conductor was antagonistic right from the get-go. One of the trumpet players, I think it was Sam Noto, said ‘do you want us to follow you or the drummer?’ First shot across the bow, you know.”

“ ‘What are you talking about,’ the conductor said, ‘the drummer’s following me. You follow me!’ “

There was another festering problem.

“During rehearsals, the mics were live. The “pit” was covered, so the musicians couldn't be seen. But they could be heard. The conductor heard what he thought were musicians talking too loudly. He yells ‘stop talking!’ “

But according to musicians and others who were there, it was actually a technical problem with the sound that was making him think the musicians were talking. They weren’t.

Fast forward to the dress rehearsal the night before the show opens. There is a partial audience. Again, the conductor thinks he hears talking. His frustration boiling over, he yells again, ‘no talking!”

Occhipinti: “So here we are in the dress rehearsal, there’s an audience out there, and one of the brass players leans into a mic and says, ‘Why don’t you fuck off?’

“The conductor says – ‘who said that?’ I’m paying you to play and not talk.’ So then Jack, because this guy had been browbeating us all week, stood up, looked at the conductor, and said ‘why don’t you fuck off with that bullshit, you asshole.’

“Jaws dropped, of course, because Jack was a pretty even-tempered guy. But then he sat down in his chair and refused to play. Then there’s a five-minute lull, and we’re trying to figure out what to do. We go upstairs and we read the riot act to Peter Appleyard. We tell him this conductor’s gotta stop hounding us or we’re not gonna play tomorrow night. We quit.”

“So we’re in the show the next night, we get through it, and the guy stops hassling the musicians. That was Jack standing up for us. He was just a really great guy. He was all business, great sense of humour, a total professional.”

"I’m not sure I’d’ve lasted in the studios without Jack Zaza.” - Barry Keane

(session drummer well-known for his work with Gordon Lightfoot and Anne Murray)

“I had very little musical knowledge when I got into the studio scene…I couldn’t read music to save my life. There was more than one occasion when Jack was there to bail me out. A couple of times he was the only reason I made it through a session. Probably a huge reason why I got hired again.”

“Way back early in my career, I somehow got booked to play for a CBC Radio series that was based on music from around the world. Well, my knowledge of music from around the world was limited to whatever pop music I heard on a transistor radio or a car radio, so I was immediately in way over my head."

“The first track we played was a Greek ditty that was way up tempo, and it was in 9/8 time. I was in so far over my head I was embarrassed, it was so awkward – I had no idea what to do. And after the first take, the arranger and most of the other musicians were looking at me like, ‘what the hell are you doing?”

“During my angst of trying to figure out what to play, I did notice, sitting right outside the drum booth, was Jack Zaza, who was playing a bouzouki part. And he was stumbling and fumbling, making mistakes galore, and during the whole time he was smiling and having the best time of his life.”

“And Jack recognized what trouble I was having - he put the bouzouki down, came into the drum booth, tapped out a drum part that I could actually hear and could play. He saved my butt on that. I was then able to make sense out of the music and play something.”

“But here was a man who was having difficulty enough with his own part, and rather than spend the next few minutes before the next take trying to figure out what HE was going to do, he took the time to come in and help a struggling drummer get through the session. Talk about kind and considerate. The other thing that stands out - here he was, stumbling over his own music, but even so, he had the biggest smile on his face, and he was laughing over the challenge he had in front of him playing that bouzouki part.”

“I can remember another time we were doing an album with a major Canadian country music star. I wasn’t all that familiar with country music, although the rest of the guys were a lot more up on the stuff. Anyway, we got to a tune that everybody else seemed to know, and it just sort of fell together because everybody knew it. So I jumped in, just playing what I felt.”

“As it turned out, the major riff in this tune was falling in a different place in the bar than where I was hearing it. So somehow, I was managing to turn this simple country tune into a bizarre polka, I guess…a few bars in, the singer threw up his hands and said, ‘what is going on?’ So everybody looked at me because they knew I was the problem.”

“I looked over at Jack, because he was playing bass on the session, and he was laughing his butt off. He knew what was wrong. Jack put the bass down and came into the drum booth. He says, ‘do you know what the problem is? I said no. He said ‘the problem is you have too much “feel.” The problem isn’t you, it’s the way it’s written.’ And then he hummed the riff to me so it made sense to me. He was able to come to a young musician and fix the problem, make me feel good, and actually fill me with confidence.”

“Most of us accept challenges. He SOUGHT challenges. He learned new instruments all the time, and he had the best time when he was confronted with difficult music on instruments he barely knew how to play. He’d go learn how to play them. He did everything with such joy."

“Such a fun memory.” - Howard Baer

Howard Baer (arranger, producer, conductor, Juno winner) was another decades-long Zaza partner in many recording studios.

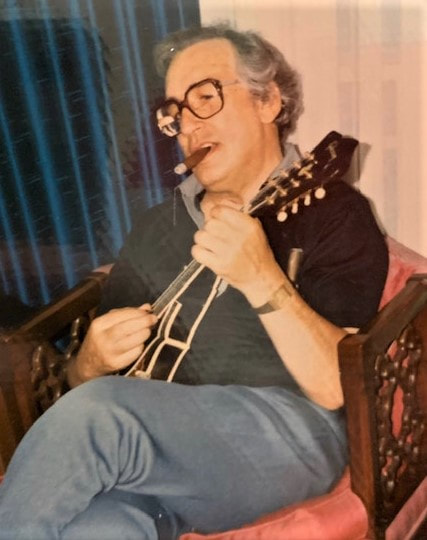

“Everybody knew him; everybody loved him. He always brought extra instruments to a recording session, because (a producer) might not realize that a tune would benefit from an extra track of bass harmonica, or mandocello, or spoons. He loved to play the spoons. And he grinned from ear to ear while he did."

"On one orchestral session that I led in the 70s, he played spoons to a fun French-Canadian tune. At the end, he waited for a couple of beats after the final chord, and then, on purpose, dropped the spoons, which made quite the clatter. The entire orchestra laughed and we kept all of it in the final mix. Such a fun memory.”

“Jack was so supportive of me and my career. He played my music so beautifully. He stayed late (at no charge) to fix stuff that he wasn’t happy with. He introduced me to important folks, booked me for live gigs, gave me stuff, welcomed me into his home. At break time, he hung with the musicians, cracked jokes, told stories, asked about what everyone was into, and occasionally went out to his car to enjoy a big ol’ cigar.”

“As giving as he was, he knew the value of the music that he and the musicians he represented were providing. When he quoted on a job, and they said, ‘oh, we don’t have the budget for that,’ his response was, ‘well, get back to me when you do.’ “

“Everybody knew him; everybody loved him. He always brought extra instruments to a recording session, because (a producer) might not realize that a tune would benefit from an extra track of bass harmonica, or mandocello, or spoons. He loved to play the spoons. And he grinned from ear to ear while he did."

"On one orchestral session that I led in the 70s, he played spoons to a fun French-Canadian tune. At the end, he waited for a couple of beats after the final chord, and then, on purpose, dropped the spoons, which made quite the clatter. The entire orchestra laughed and we kept all of it in the final mix. Such a fun memory.”

“Jack was so supportive of me and my career. He played my music so beautifully. He stayed late (at no charge) to fix stuff that he wasn’t happy with. He introduced me to important folks, booked me for live gigs, gave me stuff, welcomed me into his home. At break time, he hung with the musicians, cracked jokes, told stories, asked about what everyone was into, and occasionally went out to his car to enjoy a big ol’ cigar.”

“As giving as he was, he knew the value of the music that he and the musicians he represented were providing. When he quoted on a job, and they said, ‘oh, we don’t have the budget for that,’ his response was, ‘well, get back to me when you do.’ “

“He was the godfather of studio musicians.” - Mike Francis (session guitarist)

“He was the cheerleader, he was the backstop for everybody, he always had the one-liners, he was always sittin’ there laughin’ and playin’ his ass off all at the same time. He was the guy you went to if you had a problem, a question, the guy who explained things to you, took you aside and give you some advice in a very kind and friendly way.”

“When I started, I didn’t know anything. I had taught myself how to play - never had a lesson. I didn’t even know what a (commercial) jingle was. I couldn’t even read music, which was a must for studio musicians. I stumbled and scuffled through my first session. I held everyone up because I couldn’t read, and I figured no one would ever hire me again.”

“But I got some more work, and Jack was always on these sessions. I was holding these guys up, and while nothing was said openly, there was this underlying feeling that this kid had better improve. And fast.“

“After one of these sessions, Jack takes me outside and says, ‘if you want to do this for a living, you’ve got to learn to at least read eighth notes.’ He’s being very kind and pleasant. He writes down the names of two books.” They were full of exercises for Mike to work on. He was advised to work with his metronome, start slow, and work his way through it until he got a handle on things.

“I got the books and spent eight hours day with them. I was still playing in bar bands bars six nights a week, so I’d be playing bars at night and working on learning how to read music for eight hours during the day. I was busting my rear end because I wanted to be a studio musician so badly. As I’m doing this, I kept running into Jack almost every day. He’d put his arm around my back, and say “Hey man, you’re reading better all the time. It’s working, man, keep doin’ what you’re doin’.’ A real father figure.”

“When I started, I didn’t know anything. I had taught myself how to play - never had a lesson. I didn’t even know what a (commercial) jingle was. I couldn’t even read music, which was a must for studio musicians. I stumbled and scuffled through my first session. I held everyone up because I couldn’t read, and I figured no one would ever hire me again.”

“But I got some more work, and Jack was always on these sessions. I was holding these guys up, and while nothing was said openly, there was this underlying feeling that this kid had better improve. And fast.“

“After one of these sessions, Jack takes me outside and says, ‘if you want to do this for a living, you’ve got to learn to at least read eighth notes.’ He’s being very kind and pleasant. He writes down the names of two books.” They were full of exercises for Mike to work on. He was advised to work with his metronome, start slow, and work his way through it until he got a handle on things.

“I got the books and spent eight hours day with them. I was still playing in bar bands bars six nights a week, so I’d be playing bars at night and working on learning how to read music for eight hours during the day. I was busting my rear end because I wanted to be a studio musician so badly. As I’m doing this, I kept running into Jack almost every day. He’d put his arm around my back, and say “Hey man, you’re reading better all the time. It’s working, man, keep doin’ what you’re doin’.’ A real father figure.”

“Jack realized her behavioural problems stemmed from her family life.” Brian Barlow

The Toronto Musicians Association chose Zaza for its Lifetime Achievement Award in 2022. Brian Barlow (drummer, percussionist, Grammy winner) was his nominator.

“As Jack became less busy in the studios, he hooked up with one of the Toronto school boards and taught woodwind instruments to high school students. He was teaching at Etobicoke School for the Arts when my daughter, Emilie-Claire was there. He told me a story about the first day of class one year.”

“Eleven clarinet players came into his classroom and one of them had the instrument out of the case and was blowing away as loud as she could, squeaking and squawking so loudly that Jack couldn't be heard giving his initial welcome to the class. He asked her to stop but she refused. He finally went over and took the instrument out of her hands. She wasn't pleased and had some nasty things to say to him.”

“Rather than sending her away, or calling the office, he asked the class if they'd like a spare period. They were thrilled with the idea and everyone got up to leave. Jack pointed to the girl and said, ‘everyone but you.’ She stayed behind. He then sat down and took her clarinet apart. He gave her back just the mouthpiece and said, ‘blow into this like you were when you came into the classroom.’ She did. He said, ‘Now you're actually doing everything correctly and you're getting a great sound.’“

“He then added the first two parts back on to the instrument and told her to keep playing no matter what. He got her to finger the few keys on the second section and she was surprised that she could get some notes. Then, while she was still blowing, he assembled the entire instrument - but did it upside down, so that he could sit in front of her and finger the keys. He played some scales, then something that sounded like the opening glissando in Rhapsody In Blue. He then played a couple of little tunes, the whole while with her doing the blowing. She was thrilled.”

“Jack then said, ‘You see, you're good at this. Your parents would be proud.’ She looked at Jack and said, 'What parents? I've never met my parents.’ Jack realized right away that her behavioural problems stemmed from her family life, or lack thereof. He spent the rest of that period working with her and she eventually became the best student clarinetist he'd ever worked with. He kept in touch with her and she eventually became a medical doctor.”

“We’ll learn together.”

Brian Barlow: “Jack actually got paid to learn to play the chromatic harmonica.”

“He was doing a CBC radio series and the music director mentioned that they were going to have to bring in someone who played harmonica, because the writers had added a new character, a young boy who gets a harmonica for Christmas and learns to play it. Jack immediately told them he'd do it. The MD said, "Do you play harmonica?" Jack said, "No, but neither does the kid in the show. We'll learn together". Of course, by the next week Jack had already developed quite a bit of skill on the harmonica and went on to become the first-call harmonica (and bass harmonica) player in Toronto.”

“As Jack became less busy in the studios, he hooked up with one of the Toronto school boards and taught woodwind instruments to high school students. He was teaching at Etobicoke School for the Arts when my daughter, Emilie-Claire was there. He told me a story about the first day of class one year.”

“Eleven clarinet players came into his classroom and one of them had the instrument out of the case and was blowing away as loud as she could, squeaking and squawking so loudly that Jack couldn't be heard giving his initial welcome to the class. He asked her to stop but she refused. He finally went over and took the instrument out of her hands. She wasn't pleased and had some nasty things to say to him.”

“Rather than sending her away, or calling the office, he asked the class if they'd like a spare period. They were thrilled with the idea and everyone got up to leave. Jack pointed to the girl and said, ‘everyone but you.’ She stayed behind. He then sat down and took her clarinet apart. He gave her back just the mouthpiece and said, ‘blow into this like you were when you came into the classroom.’ She did. He said, ‘Now you're actually doing everything correctly and you're getting a great sound.’“

“He then added the first two parts back on to the instrument and told her to keep playing no matter what. He got her to finger the few keys on the second section and she was surprised that she could get some notes. Then, while she was still blowing, he assembled the entire instrument - but did it upside down, so that he could sit in front of her and finger the keys. He played some scales, then something that sounded like the opening glissando in Rhapsody In Blue. He then played a couple of little tunes, the whole while with her doing the blowing. She was thrilled.”

“Jack then said, ‘You see, you're good at this. Your parents would be proud.’ She looked at Jack and said, 'What parents? I've never met my parents.’ Jack realized right away that her behavioural problems stemmed from her family life, or lack thereof. He spent the rest of that period working with her and she eventually became the best student clarinetist he'd ever worked with. He kept in touch with her and she eventually became a medical doctor.”

“We’ll learn together.”

Brian Barlow: “Jack actually got paid to learn to play the chromatic harmonica.”

“He was doing a CBC radio series and the music director mentioned that they were going to have to bring in someone who played harmonica, because the writers had added a new character, a young boy who gets a harmonica for Christmas and learns to play it. Jack immediately told them he'd do it. The MD said, "Do you play harmonica?" Jack said, "No, but neither does the kid in the show. We'll learn together". Of course, by the next week Jack had already developed quite a bit of skill on the harmonica and went on to become the first-call harmonica (and bass harmonica) player in Toronto.”

“He never backed down from a challenge.” - Jackie Pardy

Jackie Pardy is Jack’s daughter. “Early mornings…my alarm clock was him warming up on the flute before he went off to the recording studio. I can still hear the arpeggio he would play as his warm-up. He was an early riser…he’d warm up, and then he’d go off to work every morning like anyone else’s dad, but he’d be going to a recording studio.”

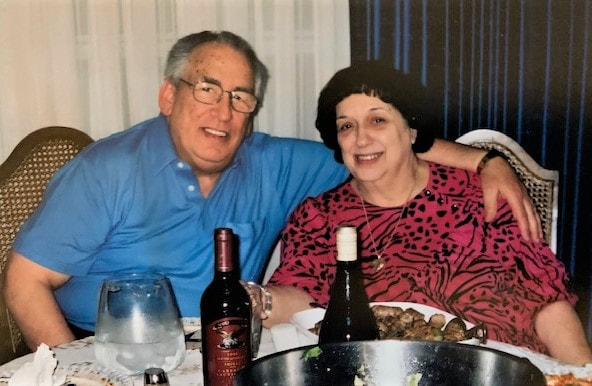

“He was a fantastic musician, but what he was most proud of was his family life. You know, he was the father of six kids, devoted husband of 70 years, he was Catholic and devoted to his faith. Not what you think of sometimes when you think of musicians.”

“He was a fantastic musician, but what he was most proud of was his family life. You know, he was the father of six kids, devoted husband of 70 years, he was Catholic and devoted to his faith. Not what you think of sometimes when you think of musicians.”

“I learned a lot about my dad in the last few years, and particularly since Mom died - just seeing how he handled that challenge. It made me realize why he’s been so successful all his life. He never backed down from any challenge. All those instruments. If someone asked him to play something he didn’t know how to, he learned how to.”

“After Mom died on April 7, he was in hospital for thirteen days. He was just so off-schedule, lots of commotion around him, and he got dehydrated. When he got out, he was determined he was going to come back. He exercised, he was like a dog on a bone about wanting to drive again, he was determined to put the weight back on that he’d lost. He started walking again. He was so proud that was able to once again walk around the block. And the morning he went into the hospital before he died, he was so proud to have done 4,000 steps.”

“He loved to learn. He even learned how to do internet banking in his eighties. After Mom died, I’d get a call now and then about how he’d finished his latest “Wordle.” He never gave up. He never had the sense that he couldn’t do something. Such an optimist till the very end.”

“After Mom died on April 7, he was in hospital for thirteen days. He was just so off-schedule, lots of commotion around him, and he got dehydrated. When he got out, he was determined he was going to come back. He exercised, he was like a dog on a bone about wanting to drive again, he was determined to put the weight back on that he’d lost. He started walking again. He was so proud that was able to once again walk around the block. And the morning he went into the hospital before he died, he was so proud to have done 4,000 steps.”

“He loved to learn. He even learned how to do internet banking in his eighties. After Mom died, I’d get a call now and then about how he’d finished his latest “Wordle.” He never gave up. He never had the sense that he couldn’t do something. Such an optimist till the very end.”

with great granddaughter Addison Zaza at the keys

Jack Zaza died of natural causes on June 24, 2022, family at his side.

Jack Zaza died of natural causes on June 24, 2022, family at his side.